This post is part of the Spreadable Startup Series, which tells stories of entrepreneurs trying to change the world. The series is made possible by Spreadable. Each week we will profile a new company and help them spread the word! Want in? Apply here.

This post is part of the Spreadable Startup Series, which tells stories of entrepreneurs trying to change the world. The series is made possible by Spreadable. Each week we will profile a new company and help them spread the word! Want in? Apply here.

The Blank Label story has it all – student entrepreneurs turned college dropouts, early failures, visa expiration, the New York Times, and a mysterious remote CTO. It’s the kind of story you hear about second or third hand at startup event or late night at the bar.

The Blank Label story has it all – student entrepreneurs turned college dropouts, early failures, visa expiration, the New York Times, and a mysterious remote CTO. It’s the kind of story you hear about second or third hand at startup event or late night at the bar.

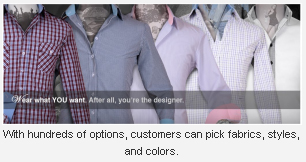

The story begins with Danny Wong and Fan Bi, two young entrepreneurs who found themselves working in Babson College’s summer incubator program on an idea they hoped could transform the men’s fashion industry. Wong, a natural DIY’er who used to paint his own clothes in high school, saw an opportunity for custom mens suits and dress shirts. The first orders, manufactured in China, began to reveal the difficulty of such an operation. “You might order a blue shirt and get a blue striped shirt,” says Wong. “Or you might order a monogram that says ‘BDB’ and get ‘BDG’ instead. We were spending a lot on re-orders, and that pretty much ate up our margin.” It was time for the first major pivot.

Realizing that both customer tolerance for slight inconsistencies and margins were greater with dress shirts than suits, the duo decided to shift their focus exclusively to that aspect of the business. As the summer ended, there were other factors to account for as well – Danny needed to decide whether or not going back to school was in his favor, Fan’s student visa was about to expire, and the team needed to grow, particularly on the technology side.

With things changing rapidly and revenue only trickling in, it was time to decide whether to throw in the towel or double down. In true entrepreneurial fashion, the crew decided to go all in. After returning to Australia long enough to secure another visa, Fan decided to take it upon himself to move to Shanghai, China, in order to take a closer look at the company’s supply chain. And, after a long and difficult search, the company found a technology lead, based in California, who agreed to help them build the technology they needed. Known mostly as “Z,” the company’s now CTO maintains a somewhat mysterious profile. “He’s an interesting guy,” says Wong. “I’m not really sure how to describe him. But he was able to build what we needed in a third of the time we’d been quoted by other firms, and he did it for free.”

With the technology in hand, the crew started moving. Press buzz started to build, slowly but surely, and orders started to come in. But even with Fan in China to handle the supplier relationships, everything wasn’t coasting along. Suppliers didn’t want to commit to contracts if Blank Label couldn’t supply business, and the company was taking orders at a rate of about one or two a day – not bad, but certainly not enough to sustain a business. “If you figure two shirts a day, for a total of say, $150; and a company of four people…well, you can see the math doesn’t really add up,” says Wong. But all that was about to change.

With the technology in hand, the crew started moving. Press buzz started to build, slowly but surely, and orders started to come in. But even with Fan in China to handle the supplier relationships, everything wasn’t coasting along. Suppliers didn’t want to commit to contracts if Blank Label couldn’t supply business, and the company was taking orders at a rate of about one or two a day – not bad, but certainly not enough to sustain a business. “If you figure two shirts a day, for a total of say, $150; and a company of four people…well, you can see the math doesn’t really add up,” says Wong. But all that was about to change.

Like musicians and actors, sometimes startups just need a big break. For Blank Label, it came last May. After a squall of press coverage in the previous weeks, Wong got a call from the New York Times. They were interested in the story, and after a series of interviews with both Wong and Bi, the company’s story ran in the Grey Lady’s online edition on Friday, May 14th, and was printed in the Sunday edition on the 16th. It was a day that would change everything.

After selling only a few shirts a day, the weekend saw Blank Label turn more than $50,000 in revenue. By the end of the following week, the number had topped $100,000. “This was huge for us,” says Wong. “It was really validation that people thought what we were doing was valuable, and that we had a business on our hands.” But the excitement quickly turned to dread as the crew began to wonder if they’d be able to meet demand. Fan turned to the suppliers, who agreed to commit the factory’s entire capacity to realizing Blank Label’s orders. The agreement was too good to be true. After a few days, Wong got a phone call from Bi, letting him know that there was a problem with the shirts. They weren’t going to make orders on time.

After selling only a few shirts a day, the weekend saw Blank Label turn more than $50,000 in revenue. By the end of the following week, the number had topped $100,000. “This was huge for us,” says Wong. “It was really validation that people thought what we were doing was valuable, and that we had a business on our hands.” But the excitement quickly turned to dread as the crew began to wonder if they’d be able to meet demand. Fan turned to the suppliers, who agreed to commit the factory’s entire capacity to realizing Blank Label’s orders. The agreement was too good to be true. After a few days, Wong got a phone call from Bi, letting him know that there was a problem with the shirts. They weren’t going to make orders on time.

Wong sent personal emails to hundreds of customers informing them of the company’s difficulties and offering refunds to those who wanted them. Some took him up on the offer, and while the burst of traffic was ultimately a net positive for the team, Wong acknowledges that their inability to scale orders quickly cost them precious revenue dollars.

Since then, the company relocated the whole team to Shanghai in order to stay closer to suppliers, take advantage of lower costs of living, and get a feel for what it’s like when the whole team (sans Z, of course) is in the same place. The results have been inspiring, says Wong. “It’s been very productive, having everyone in the same place.” Fan and Alec are back in Boston now, and Wong plans to join them soon. The company is self-sustaining, he says, but is interested in taking on additional capital to help scale the team, continue its technology development, and generate better margins. “We’re hoping to set up shop in Boston in 2011 and really find some great talent to bring on board.”

We’re lucky to have them back, and we’ll be expecting big things from Blank Label in the coming year.

For the original article, check out BostInnovation.com.